“Over 90% of the material cultural legacy of sub-Saharan Africa remains preserved and housed outside of the African continent”

Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics

In 2017, Emmanuel Macron publicly announced France’s intention to begin the restitution of looted African material culture back to Africa. After centuries of colonization going widely unacknowledged by France, this announcement was surprising to the people of France and the people of countries affected by French colonization.

Since this announcement, which seems to have been primarily performative, some of these stolen objects have been returned to their places of origin. But far more still sit in European museums, removed from their context and communities.

The following are two examples of objects originating from Benin and Mali held captive by the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris. One has been restituted, the other has not.

Half-man half-bird royal statue of King Ghézo:

attributed to the Donvide workshop or Sossa Dede, Akati workshop.

Fon people, Benin, Abomey. Second half of the 19th century, wood, pigments, iron

attributed to the Donvide workshop or Sossa Dede, Akati workshop.

Fon people, Benin, Abomey. Second half of the 19th century, wood, pigments, iron

Once coated with magical substances, this statue protects warriors. One of a set of three, these hybrid figures, half-man half-animal, bear the emblems of kings: the cardinal with its flame-red feathers for King Ghézo, the lion for Glélé, and the shark for Béhanzin.

Restituted in November 2021,

129 years out of context.

Composite Sacred Object, Boli, Musee du Quai Branly

This object was made between 1850 and 1930 in the Segou region of Mali. It is meant to be kept in a secret shrine, where it mitigates negative energy away from a community.

It is a composite object, made of many different materials including beeswax, animal blood, wool, and wood. It gains power when seated in its birthplace, one of the many reasons being displaced is violent and harmful to this object, its life cycle, and the people it once protected.

This object as not been restituted.

Restitution Now Stencil

Created in 2022 by Ralph Skunkie Davis

“PARIS STILL STEALS ART” refers to the refusal of Parisian government officials and arts councils to prioritize the restitution of African material culture held outside of Africa, inaccessible to a large population of people to whom these objects belong to. The stencil’s message, sprayed on walls around Paris, aims to remind tourists and locals that visiting museums and institutions is not a neutral act. By participating in tourism without acknowledging and critically engaging with the centuries of violence present in what are considered by many to be “The greatest museums in the world” (The Louvre, Musée d'Orsay, Musée du quai Branly), we are complicit in perpetuating these cycles of displacement and colonialism. By presenting this stencil as an art object within the Ecole IESA, (the negative image, rather than the positive created by the stencil) I hope to remind viewers what is missing, the context so many art objects have been removed from.

Street art is a medium of decolonial art viewing. Street art is big and free to the public, there are no security checks or police stationed at the door looking at you sideways. The adornment of public architecture is a community project. Murals like this often become the texture of a neighborhood, a meeting point, a way out, a way in. This site specificity is important to consider when viewing street art, and when viewing this project.

Street art and its role within our neighborhoods reminds me that somewhere, not too far off in reality or time, there exists an art market that revolves around the consent of the artist and the community they are invested in. A way of living off our art that is not based on a scarcity mindset, but centers art that is context dependent, deeply connected and present in its place of origin, free to grow roots and feed those who need it. To me, street art and graffiti is a promising path toward this vision. This stencil and its use around Paris, legally and extra legally, is an attempt at visualizing a society held accountable and made aware of injustices occurring within through mark making.

Explore other restitution timelines and material culture below:

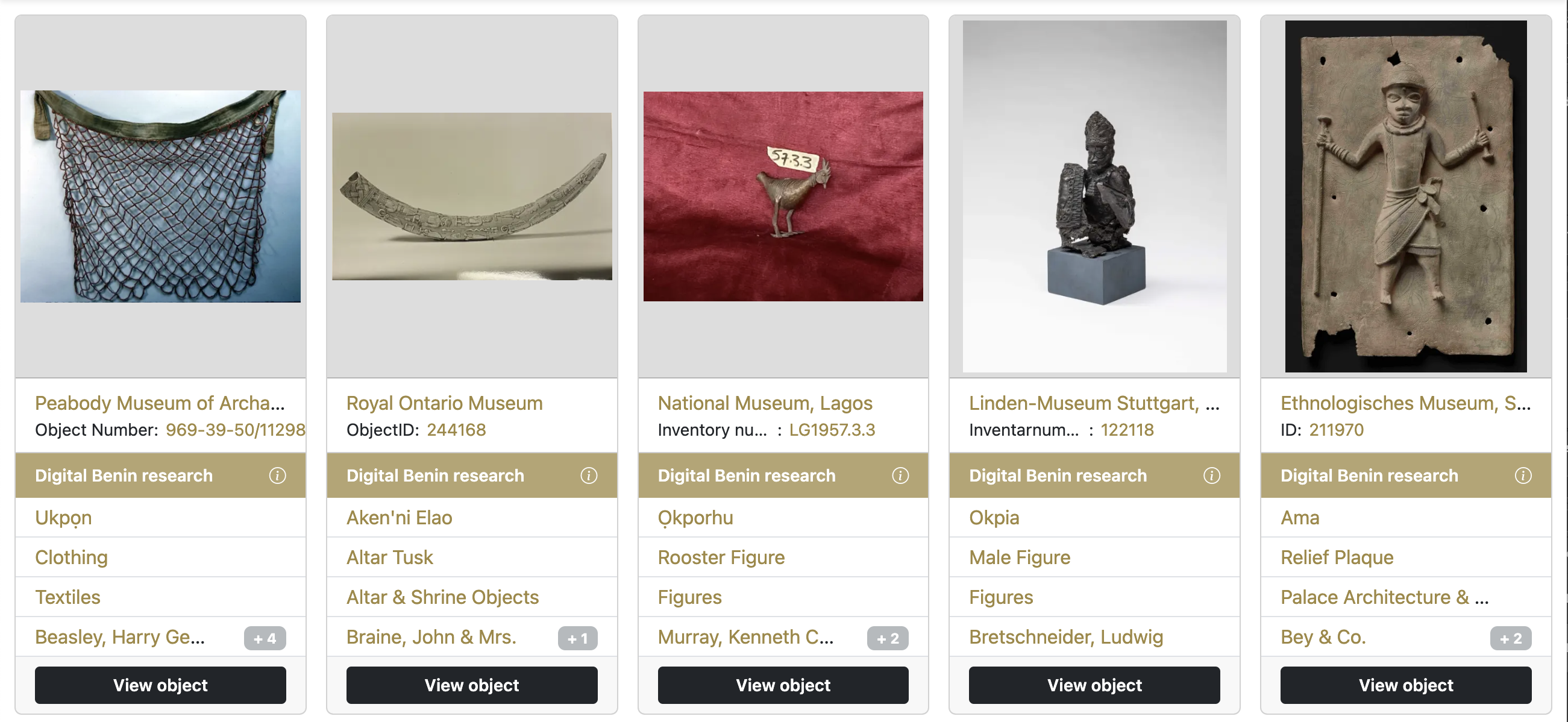

Digital Benin is an online database of culturally significant Edo artifacts created by and for those affected by their displacement. Users of the website can explore an object’s provenance, institutional seizure, and place within Itan Edo (the history of Benin Kingdom).

Citations

Sarr, Felwine, and Bénédicte Savoy. The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics. MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE, Nov. 2018. Gundu, Zacharys. Looted Nigerian Heritage-an interrogatory discourse around repatriation. Contemporary Journal of African Studies 7.1, 2020 Kirshenblatt-Gimblett. Objects of Ethnography. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian, 1991

Digital Benin. digitalbenin.org.